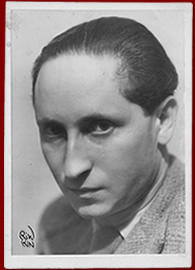

ERIC ISENBURGER was born on May 17, 1902 in Frankfurt, Germany, into a wealthy banking family. He was the younger of two sons.

ERIC ISENBURGER was born on May 17, 1902 in Frankfurt, Germany, into a wealthy banking family. He was the younger of two sons.

His memories of childhood included the time when he had measles and the doctor, fearing that the eyes might be damaged, ordered all Eric’s drawing paraphernalia to be put away out of reach. Eric resorted to making drawings on a roll of toilet paper, using the nurse’s stub of a pencil. He also recalled that once his mother urged him to invite a school mate home to play. They drank a cup of chocolate, but the boy refused the beautiful cake, saying “It’s Jewish cake.” In school Eric played the violin, but his greatest interest and activity was always drawing. Regarding family life he remembered that during World War I, a time of deprivation even for the well-to-do, his father would lock his own bread ration in the safe in his study, but Eric’s brother Herbert sometimes appropriated Eric’s loaf for himself. However, years later, in 1941, it was Herbert who paid for passage to the United States for Eric and his wife Jula.

The family wished both sons to grow up to manage and expand their banking interests, but Eric was very determined to study art. He enrolled in a Frankfurt art school and became the student of Franz Karl Delavilla. When a patron requested Delavilla to paint several individual portraits of himself and other family members, Delavilla replied that he did not have time for this project, but said “There is a student, Eric Isenburger, who can do an even better job than I can!”  Eric undertook the commission, to the satisfaction of all. When he finished the art course under Professor Delavilla, Eric went to live for a time in Spain to paint. He had a studio in Barcelona.

Eric undertook the commission, to the satisfaction of all. When he finished the art course under Professor Delavilla, Eric went to live for a time in Spain to paint. He had a studio in Barcelona.

Jula Elenbogen was born in January 1908 in Augustow, Russia (Poland after World War I). Augustow was a small village, without any school. Jula remembered her mother as a very intelligent and elegant woman, living in a rough wilderness, a land where there was almost uninterrupted fighting of one sort or another including occasional raids by cossacks. Jula recalled being sometimes posted as a lookout to warn her father. Another memory was of once fleeing with her parents in a primitive wooden wagon, during bitter cold weather. The floor of the wagon was covered with straw, but her elegant mother was “dressed as if for the opera.” They reached a large town, where her mother had an admirer who owned a chocolate factory, “and we ate almost nothing but chocolate for a week. That is why I have no liking for chocolate!” In the same town she and her parents were walking past a statue of the Madonna mounted in a wall; some men bullied her father, demanding he remove his hat to show respect to this Christian icon.

Once when her father was away there came ragged troops toward the village, marauding and raiding. Her mother was very quick-witted: as soon as she learned they were coming she ordered the cook to heat water in their largest pot (it was the one for boiling the laundry), to find all the food in the house and make a soup. The hungry soldiers beat on the door and came in shouting “Bourgeois, bourgeoise, give us your gold!” But the wonderful smell of the soup “tamed” them, and Jula’s mother fed everyone, so that they left thanking her.

As Jula herself was a bright child, she was sent to board in a larger village, Sowalky, where there was a school. She said it was very lonely and dark, and she did not remember much about it. Then she was sent to an uncle’s house in Warsaw, and finally, though she was only fifteen, she asked to go to another uncle in Frankfurt. This uncle in Frankfurt was the patron who had commissioned the family portraits from Eric.

After her years in Augustow, Sowalky, and Warsaw, Jula found Frankfurt very wonderful. There were frequent plays, operas, concerts. There was her uncle’s large library, which she undertook to catalog. She was trying to teach herself to speak and read German. She also studied piano quite seriously, until one day her teacher advised her: “If you want to see how to play piano, go to hear the concert tonight that is given by your countryman, Vladimir Horowitz.” She was soon to give up playing piano and concentrate on dancing, her first interest, where she had good success.

Eric had been living in Spain but was on a trip home, when he rang one afternoon at the uncle’s house to pay a visit. Jula’s uncle and his wife were away traveling, Jula left with the housekeeper and her young cousins. Jula answered the door herself and so saw Eric for the first time. She remembered that when Eric asked for her uncle, she quickly said “He is not here” and shut the door, but the housekeeper rushed to call Eric back–recognizing him as a special friend of the family. The housekeeper insisted that Eric come inside and then she interpreted since Jula could barely speak German.

The two young people took an immediate interest in each other. They began going out frequently, chaperoned by Jula’s aunt. Jula quickly became more fluent in German. Eric enjoyed showing her around Frankfurt and introducing her to a new world of art. Years later she sometimes would say “My life began with Eric.” Of course he himself was very enthusiastic about all that he was then learning and doing and thinking, and Jula was a very willing and intelligent student. They developed a close rapport and collaboration that was to last the rest of their lives together.

Although Jula was underage, she felt ready to marry, and her parents consented. Eric’s family were disapproving that he had chosen and married “that little Polish girl.” They stopped–or severly reduced–his allowance. As it was then especially inexpensive to live in Vienna, Jula and Eric went there shortly after their marriage in Augustow. In Vienna Eric painted, Jula danced. Eric also designed sets and costumes for the dance company. Soon they had friends–artists, dancers, musicians. Jula was a soloist in Vienna and Salzburg. Photographs from that time, as well as Eric’s paintings, show people who are intense, living for their art.

Although Jula was underage, she felt ready to marry, and her parents consented. Eric’s family were disapproving that he had chosen and married “that little Polish girl.” They stopped–or severly reduced–his allowance. As it was then especially inexpensive to live in Vienna, Jula and Eric went there shortly after their marriage in Augustow. In Vienna Eric painted, Jula danced. Eric also designed sets and costumes for the dance company. Soon they had friends–artists, dancers, musicians. Jula was a soloist in Vienna and Salzburg. Photographs from that time, as well as Eric’s paintings, show people who are intense, living for their art.

Eric’s father had died some years before; his mother committed suicide in 1931 or 1932 and he inherited. Eric and Jula now decided to move to Berlin, where artistic activity was then at its height. In the style of the day, they commissioned an architect designer to make their large atelier together with all the furniture. They had no idea that they would live there for only a few months.

Eric’s first one-man show was in 1933, at the Galerie Gurlitt in Berlin. Although enthusiastically received by the public and critics, the paintings were attacked in the National Socialist press. Wolfgang Gurlitt advised Eric that “You and Jula should take a little vacation abroad.” They left almost everything and boarded a train to Paris.

There were some months in Paris, then a long trip to Sweden, Eric painting and exhibiting all the while, Jula dancing in her own touring program as Jula Geris accompanied by a fine pianist named Elsky playing Les Six–Satie, Poulenc, etc. As before she danced in costumes designed by Eric.

With Paris becoming more and more expensive, they decided to move south to Nice, almost deserted in winter. Later they lived in Grasse.

With the fall of France Jula and Eric, like the many others who had fled Hitler’s Germany, were considered as enemy aliens. The French government was disorganized; there came an order for first men, then women, to report for temporary detention–to sort out who was who. Eric, along with several other artist-, writer-, and musician-friends, went off at this order, expecting to be released in a few days. Instead he was interned for many months.

Jula meanwhile continued to live in their little rented house in Grasse, alone with their cat but with friends close by. Soon women who had come from Germany were ordered to report, and she too was interned. Conditions in the French camps were austere but not brutal. Jula recalled lying awake in her bunk at night in the camp called Gurs and “gratefully gnawing on a little piece of bread” that she had purposely saved from the meager supper.

Because Eric was an artist and wrote a beautiful and clear script, he was set to work in the office of Les Milles drafting orders, passes and so on. He was able to forge documents discreetly but effectively. Eric also drew every day whenever he could, taking as subjects fellow prisoners and guards alike. Many guards were flattered and amused by the drawings of themselves and were glad to accept them as gifts.

Eric felt convinced that he must escape to safety. Because he had some money, having taken payment in Swiss francs for a number of paintings done before the war, he was able to bribe the right people to declare him ill and in need of hospitalization. The diagnosis was pulmonary insufficiency. He was for weeks in a hospital room. Occasionally a French official would make a visit to keep up appearances. Eric remembered that one afternoon this policeman came into the room while Eric was sitting up in bed smoking a pipe. The only comment was “I am happy to see that you are getting better!” In telling this years later Eric was to say “Everyone knew what was going on.”

Eventually Eric left the hospital. Jula had escaped from Gurs by going under a fence and taking a bus south to join Eric. They were to spend several weeks in hiding at a pension in Nice before they got visas to cross Spain. After arriving in Lisbon they waited a few more weeks until they could sail to New York.

~ Sheila Low-Beer