Studies on the work of the painter Eric Isenburger [summary]

Studies on the work of the painter Eric Isenburger [summary]

Martin Meisiek

1. Art and Life of Eric Isenburger

The painter Eric Isenburger belongs to a German generation of artists who did not witness the fame and success of the first Expressionist painters working shortly before and after World War I. After the seizure of power by the National Socialist Party in 1933 Isenburger did not fit into the system of a racially correct and German-nationalist art implemented by the NS cultural policy, just because of Isenburger’s Jewish background and his way of painting, which was rejected as to be “degenerate”. Condemned by the press and expulsed from Germany in the moment of rising success, nobody remembered Isenburger’s and his colleague painters’ former achievements after the end of World War II. The new art historical orientation towards Abstract Expressionism during the post-war time, the straining for continuity of the classical modern art and the rejection of painting close to reality contributed to this fact as well. But it is exactly the subjectivist reception of reality that characterizes Isenburger’s art. That is why Rainer Zimmermann calls Isenburger and his contemporaries exponents of expressionist realism.

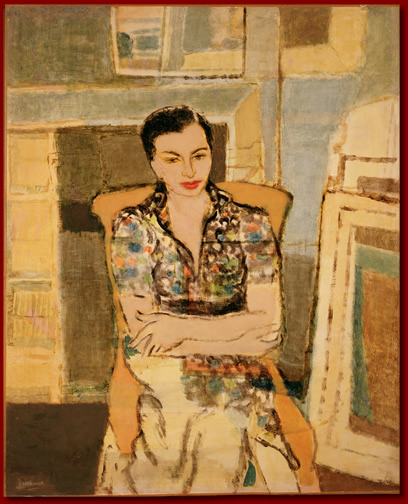

Son of a well-to-do Jewish family of bankers in Frankfurt, Isenburger had early tried out various techniques of painting, before he started his studies in 1920 in Franz Karl Delavilla’s class of graphic design at the School of Applied Arts, where he finished in 1925. Influences from the style of Isenburger’s teacher are slightly visible in some examples. Being a freelance artist in Barcelona from 1925-1927, he painted in all common genres, but turned towards portraits by the time he marries Jula Elenbogen and moves to Vienna with her. There he integrates elements of Viennese Art Deco and Expressionism in Oskar Kokoschka’s style.

Having inherited in 1931, the Isenburgers moved to Berlin where they lived in a newly designed studio. The topics of a lot of Eric’s paintings were dancers whose shape is nervously and thinly scratched on the canvas. His first solo exhibition at Wolfgang Gurlitt’s Gallery in January 1933 had good reviews, but also got harsh attacks from the NS press, so that Eric and Jula quickly fled to Paris on Gurlitt’s advice. In the French capital, Isenburger started with experiments in abstract and surrealistic painting. His exhibitions in London and Stockholm show a gradual transformation of his portrait conception towards brighter colors and broader space. The interiors, landscapes and still lifes created in the south of France around 1937/38 prove the influence of the great French masters of modern painting like Monet, Cézanne, Matisse and Bonnard. During his one-year internment in Les Milles and St.Nicolas he produced forceful portrait drawings of other internees, often intellectuals and artists like him. Without any break, Isenburger took up his manner of French-styled paintings after the successful emigration to the United States in 1941. In the mid-40s he gave up interior painting, which had meant a lot of success to Isenburger, and turned towards a concept of landscapes comparable to Van Gogh, which he followed up to his latest works. The mid-40s were also the time of self-portraits: they reveal Isenburger’s existential and artistic turnover during that time. The simultaneously produced figural paintings and the scenes on memories of the painter’s trips to Europe and to Central America show Cubist ideas taken from Braque and Picasso.

Having inherited in 1931, the Isenburgers moved to Berlin where they lived in a newly designed studio. The topics of a lot of Eric’s paintings were dancers whose shape is nervously and thinly scratched on the canvas. His first solo exhibition at Wolfgang Gurlitt’s Gallery in January 1933 had good reviews, but also got harsh attacks from the NS press, so that Eric and Jula quickly fled to Paris on Gurlitt’s advice. In the French capital, Isenburger started with experiments in abstract and surrealistic painting. His exhibitions in London and Stockholm show a gradual transformation of his portrait conception towards brighter colors and broader space. The interiors, landscapes and still lifes created in the south of France around 1937/38 prove the influence of the great French masters of modern painting like Monet, Cézanne, Matisse and Bonnard. During his one-year internment in Les Milles and St.Nicolas he produced forceful portrait drawings of other internees, often intellectuals and artists like him. Without any break, Isenburger took up his manner of French-styled paintings after the successful emigration to the United States in 1941. In the mid-40s he gave up interior painting, which had meant a lot of success to Isenburger, and turned towards a concept of landscapes comparable to Van Gogh, which he followed up to his latest works. The mid-40s were also the time of self-portraits: they reveal Isenburger’s existential and artistic turnover during that time. The simultaneously produced figural paintings and the scenes on memories of the painter’s trips to Europe and to Central America show Cubist ideas taken from Braque and Picasso.

Eric Isenburger died in 1994 at the age of 92, several times honored by the National Academy of Design, where he had been teaching for a long time, and represented in numerous exhibitions and museum collections all over the country from the very start of his career in the United States. After the death of his wife Jula in 2000, the Eric and Jula Isenburger Society took care of his artistic heritage and made research on his earlier works lost to a big part after his emigration to the United States.

Interestingly, you can see a kind of anti-cyclic relation between biographical breaks and Isenburger’s artistic and stylistic continuity: often changes are barely visible in his works of transitory periods: not only after he had escaped to Paris but also after his emigration to the USA he always developed his new works referring back to former achievements. The portrait Jula standing (1932) was painted in a style of thin, white shapes; the painting Jula in blue (1933/34), probably created in Paris or Stockholm, smoothes down the white shape line and comes to more intensive colors, worked out from a dark background. In spite of his internment from 1939 to 1940 he restarted with interior paintings in New York in 1941, integrating people or landscapes, just like in the post-impressionist style of his period in the Southern France (cp. At the piano (1937) with On the terrace (1941) and Vue de la Ferrage (1938) with Queensborough Bridge (1945)). Changes can be pointed out during periods of external safety and prosperous artistic work: the turn towards interiors, brighter colors within the paintings and a new sense for landscape pieces took place after Isenburger had moved from Paris to Nice. The new daring use of colors in the late 50s went together with a time of great artistic acknowledgement in the USA.

The results of this thesis can lead to further questions and important extended research projects. However, Isenburger’s live as an artist in Barcelona, Vienna and Southern France has to be cleared as well as the still unknown works of this time.

The American paintings should be available more easily as they can be found in museum collections or in his artistic estate of New York.

A general call for Isenburger’s works in newspapers or on the Internet may lead to further explorations that can help to verify or falsify the suggested analogies to exponents of classical modern painting. A most extensive catalogue of Isenburger’s paintings should be the ambitious aim for any further studies on this impressive and charming artist of the 20th century.

2. Eric Isenburger and the 20th century painting

The analysis of Isenburger’s paintings shows a great variety of artistic influences throughout his career. Between 1924 and 1989 he realized sujets and picturesque genres of high continuity. Apart from landscapes, still lives and interiors it was the portrait that he especially preferred. These works centered during his time in Berlin and Vienna and during the 50s and 60s in America. The self-portraits of the 40s convey an Isenburger who was occupied with a self-study of psychological changes, ranging from fear to self-confidence. He knew ingeniously how to transform the portrait into figural painting (e.g. Dancing Africans, around 1932) or to integrate them into his interiors (USA, beginning of the 40s). But even his late works reveal transitions: landscapes and floral still lives go together into an interchanging pictorial concept.

Most of his early works dating from the time until he escaped to France are marked by the expressionism of Viennese style. It was his teacher Franz Karl Delavilla, exponent of the Viennese Art Deco in the early 20th century, who influenced his study works. Klimt’s, Schiele’s and especially Oskar Kokoschka’s “school” led Isenburger to a sense of form and color that had a tremendous effect on his most individualized portrait style in scratch technique (e.g. Portrait Wolfgang Gurlitt, 1932/33), which he perfected in Berlin. In France Isenburger came in touch with a lot of new approaches that had the most lasting effect on his style and his choice of topics. Picasso’s and Braque’s cubism and the surrealistic inspirations of Max Ernst brought the painter to a short experimental phase of abstraction, which he took over once more in the 50s working on his impressions of trips to Europe and to Central America (e.g. bullfights in Mexico). In all these periods one remarks the predominance of the line instead of color and tone. Isenburger’s art changed when coming into contact with light and landscape of Southern France. Monet’s and Bonnard’s late impressionism as well as Matisse’s fauvism had a tremendous impact on the arrangement of landscapes and interiors of that time (e.g. View from La Ferrage, 1938 or At the piano, 1937). Especially interiors could only be developed in a surrounding of light-flooded rooms. This picture genre became only obsolete in the mid 40s when Isenburger intensified color and brushstroke on Van Gogh’s tracks (e.g. Gran Manan, 1946) and when subdued tones and plain canvas structure were not any longer practicable.

It was Cézanne who initialized Isenburger’s turn towards a new conception in still life painting (up to almost direct quotations from Cézannes works, e.g. Still life with sculpture, 1935/37) between the mid 30s until the late 40s. Thus, Isenburger is a painter keeping up the tradition of the great French masters of classical modern painting, which he partly knew to combine with the language of Viennese expressionism. He often picked up elements with a big time delay like the japonism that has known a certain revival in Isenburger’s late works, one hundred years after Bonnard (e.g. Model with Kimono, 1989). He never was a simple epigone of these masters, but yearned for a creation of harmonic and dream-like pictorial universes, which seldom lose their link to reality. He was able to transform the sometimes harsh and revolutionary stylistic and topical elements coming from his artistic examples into a smoother and reclining expression. He never tried to display psychic extremes of his portrait models in Kokoschka’s sense, he never deconstructed objects as consequently as Picasso or Braque and he never had such a strong impetus in his American landscape painting as Van Gogh. Isenburger shared all the problems that the masters of modern painting were faced to as well as the solutions they found. But he knew how to transform them in his personal manner of expression that seeks for an atmospherical harmony and the real being of the things in a less spectacular but more poetic way. His concept of “sub-pictures” together with the technique scratching on the surface of these things that he had developed over a long period of time is one of his major achievements.

If you want to put Isenburger in accord to Zimmermann’s style construct of expressive realism1, you may call him an exponent of a subcategory, the poetic realism, whose name is especially due to Isenburger’s works of the mid 30s in Southern France up to the late 40s in the USA. Zimmermann calls poetic realism “the trial to make poetic substance of every kind of reality comprehensible. Exactly the simple things, the every-day actions are its preferred motifs. Their poetic aspects can utter either in the spatial quality of their being or in the harmony of the color tones on the painting ground.”

This is but an approximate classification of Isenburger’s highly individualistic style. Therefore, Rainer Zimmermann says that expressive realism is not a style but a basic approach of an artist.

Martin Meisiek, Studies on the work of the painter Eric Isenburger (1902-1994), Exam Thesis (Summary) University of Regensburg Department for Art History, 2003