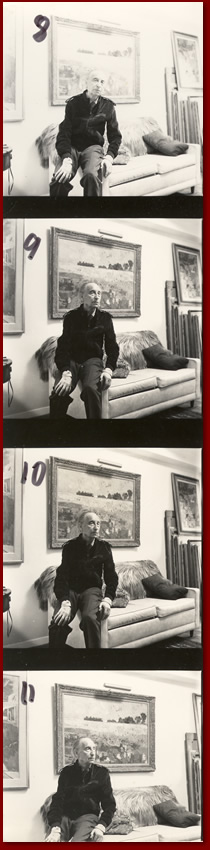

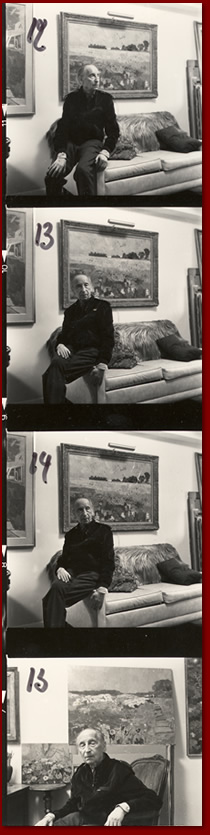

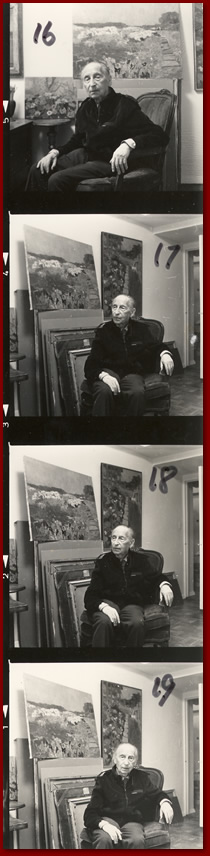

Interview by Karl E. Fortess (Boston University, School of Fine Arts) and Eric Isenburger September 12, 1975

In 1968 Professor Fortess was commissioned by the Office of Education from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare to develop a collection of taped interviews of American contemporary painters, sculptors and architects.

Eric Isenburger has been painting for over 50 years. In that time the number of changes in the different isms has been going through the whole history of art. Has it affected in any way your work today?

Eric Isenburger has been painting for over 50 years. In that time the number of changes in the different isms has been going through the whole history of art. Has it affected in any way your work today?

It has affected me especially in the beginning. Right then I was under the influence of the Bauhaus, which you can’t see any longer. And when I got out of art school, which was in Germany, I went to Paris and I was under the influence of everything else but expressionists and so on. I came under the influence let’s say of the cubists as well as neo-impressionists as to say Matisse and Vuillard. And those are the ones that I admire most even today.

These have been described as intimists. A very intimate kind of painting…

Yes, the early stages were the intimist stages, but later on they were called the “Nabis”. But I simply called them neo-impressionists because they had something in common with the impressionists though they might have gone very much further by using nothing but flat paint, flatness…the main theme. And I was very impressed by it and I am still going this way. Maybe it doesn’t look it so much but still…

You remain in that tradition.

Yes, I remain in that tradition somehow.

So you say you were influenced by the Bauhaus. Does that mean that you actually studied at the Bauhaus?

No, I didn’t, I studied at Frankfurt. But everybody dreamt about Klee and Kandinsky. And you were sort of pushed into this direction without wanting to go there. Or even if you wanted to go there it was only for a short time.

But you nevertheless must have received a fairly traditional education in terms of your drawing and your studies.

We were taught the fundamentals in everything, in that Germanic way that said: “You had to if you want it or not.” Otherwise there was no choice. It was very, very, very severe, of course.

Was there any possibility of revolting against this tradition and going toward Kandinsky rather than the Germanic training for craftsmanship and color and design?

After you had your let’s say three or four years studying fundamentals you could go; even you were driven to go into this group of let’s say Klee – Kandinsky – Campendonck and a few others. But not everybody in class did, of course. Some went for the expressionists, of course: Nolde and Schmitt-Rottluff very much en vogue…

…Haeckel…

…Haeckel and Kokoschka, and these also have influenced me to a large degree…at that time of course in my early twenties.

But this was done on a basis of a fairly traditional way to draw and to paint?

Yes, in a manner of speaking. That is right.

You could qualify by making your life studies which passed muster with your professors so that if you deviate from it and become completely non-figurative as in the case of Kandinsky you still have this background?

Yes, you have the background. Some did for instance… they…became abstract painters at the very same school.

I am curious what your opinion is: could you have become an abstract painter without that traditional background?

No, no. The traditional background was demanded and an absolutely necessity. After that you could do what you wanted. And I actually started out with painting abstract. As you say sort of protest. Everybody that is 22 years old wishes to protest. But I came back to what I called reason and I painted from the beginning on paintings that would be leading to what I am doing now. There are only several developments.

But essentially you could be described as a painter involved directly from nature or indirectly from nature?

But essentially you could be described as a painter involved directly from nature or indirectly from nature?

Indirectly from nature….Nature is done from nature; it is done from stages and so on. Little studies. I mean there are little studies from nature, not little copies from it.

Does working from nature have any kind of problems as opposed to working in the studio?

Yes, there are some minor problems like sunlight and glare that can disturb. And also if you paint directly you don’t have enough distance from the work. You have to go home and think about it and probably do it again after what you did from nature. I had to redo it or I had to turn back to nature and paint right out of the room or so and look occasionally for a longer time and get an impression of what I look at.

But nature is essentially your experience.

Nature is essentially my experience, that’s right.

Do you translate in your own terms in your own studio?

Yes.

Now this is a question you may not like because people don’t like labels. But what kind of label would you find most comfortable with as a painter? You always have to be classified for some reason.

Yes, I know, I know. It’s very difficult in my case, but I would say simply one sort of a neo-impressionist.

Would you add the word “romantic” to it?

Yes, in many cases.

In your paintings as you say you have gone through a number of influences. Also as a teacher how do you feel, what is the importance of an influence for a student?

The importance is, after we have taught or dwelt on the fundamentals, the student should find a way of expressing himself which is the most difficult of all. You can only give a lead but you mustn’t push someone in one single direction and certainly not in your own because each single student has his own character, an outlook on the world, of course. And the difficulty for a teacher is to find what is that outlook, like which is it. And so every single student in my class paints his own way. Of course I try to get them to draw well.

But they do not work in imitation of your work, do they?

No, they don’t. I try to keep them away from my things.

Another question: we always associate “Germanic” with a very stern kind of discipline. And now as a painter: are you a disciplined individual in terms of your own working schedule?

Yes I am. I paint as often as possible and only in the morning from 8 till 2 let’s say, long hours, or from 9 to 2:30, something like that, it’s more or less the same. I do always keep this kind of a discipline, I very much believe in it.

Do you ever have periods of time when you simply cannot work? Do you have dry periods?

Oh, certainly, that everybody has to have…that you can’t go on!

How do you get out of these?

Well, not giving in. And try again, try again. Do not give in.

Do these periods last a long time?

Do these periods last a long time?

No, they didn’t. In my case they didn’t. I know an artist where they lasted up to a year! I have known Bradley Tomlin in Woodstock and he said such a terrible thing that happened to him. He couldn’t paint for a year.

You are more fortunate. You overcome this by doing what? By working?

By insisting on working! If a new work doesn’t come off I take an old one and paint on that.

But you use the studio to get yourself out of this period?

Yes I do.

Do you work on more than one canvas at a time?

Very rarely I must say. I don’t like to do it. But in those dry periods as you very well describe them I might have two or three canvases going at the same time. They are usually all painted when I continue painting on them.

Do you complete each picture that you started?

Yes, I try to do it.

What period of time do you use for making sketches? Do you live in the country, do you go out to observe in any particular fashion?

Yes, we are going very often for two or three months in the summer to the country, sometimes here in the United States and quite frequently in Europe. We’ve been to France and to Spain, to Italy.

And this is for collecting material and impressions of…?

Yes, I am sketching mostly abroad, but also painting.

Does that mean you carry your sketch book with you?

Yes, I have a number of sketch books with me.

And when you say you paint during these travels you work in oil when you do that?

Yes I do. I used to do it in pastel, but the pastel translated into oil always becomes pastel. So I did not do it. I did not continue with that. Also watercolour I do not do. As preliminary I do two or three drawings of one and the same idea and develop the drawing first before I paint it. But by the time I come back let’s say to New York I can…paint it.

And this preliminary work…is this the work that you use other than for your own background of your pictures and your drawings? I mean you show drawings and you show watercolors.

Occasionally I show drawings. I have also shown pastels.

Are you involved in any peripheral activity painters have like making prints, etching, lithographs, that sort of thing?

I have done some etchings and lithographs.

And did you enjoy it?

Yes, I enjoyed it very much….

You spoke about pastel as a medium. Are you curious about the newer mediums, the acrylics, the plastic pigment of any sort?

No, I dislike them intensely. But I have seen students of mine working with them and one or two handled it very well, but they handle it exactly like oil. When they handle it as let’s say acrylics it becomes posterly, not painterly. And therefore I don’t like it because it becomes so hard and so harsh.

Would you say it has a brittle quality, hard edge kind of thing?

Yes, they have, exactly.

And you find the oil is a medium that you find yourself more sympathetic to?

Yes I do.

Now this is another question that is maybe difficult for you to answer: your percentage of success with the canvases you work on, how does it run? Do you complete every canvas you begin?

I might complete every canvas I begin. But then I destroy very many afterwards, let’s say after 5 or 6 or 7 years only. And I don’t keep everything I do. As a matter of fact I keep perhaps not even every second painting. That few.

And after all these years of painting experience you still have that problem?

Well, I am quite severe with myself. I think the later paintings I almost all kept. But pictures of 10 or 15 years ago I still destroyed.

Have you ever been sorry that you destroyed work of yours? Not to be able to look back where you have been?

No, I haven’t been sorry. I am glad that they are all away. Once a decision is done it should be done. Well, other painters have done that through all. Rouault maybe only two years before he died he destroyed 80 of his works. And he certainly had no regrets I am sure.

Now I understand this standard is something you said about yourself; the art world society has no way of affecting you this way?

No, they have nothing to do with that. Nothing. There are certain things I don’t want to have run. When I see that they definitely do not come up to the work that I am doing and I cannot improve, then I destroy it. There is no other choice.

That’s a very severe strategy you set for yourself!

It is, I know.

Is it the same standard for your students when you deal with them?

No, I don’t want to discourage the students, absolutely not. They need nothing but encouragement, more than anything else. And I don’t even tell them these things. They are sort of my own secret.

Students may see this and your secret will be out.

(laughing) I will never be all right. I hope it won’t discourage the students.

Do you think a student could be discouraged by what somebody else says? Do you think that it is necessary that a student should fight his… or her way (there are also women, of course)? Do you think that if you could discourage a person from becoming a painter…that this person would not want to become a painter? Do you think they could fight their way through you?

Yes, I hope that they would do. But I have never discouraged anybody…

Your own teachers, were they always encouraging when you were a young man?

I tell you they were not. No.

Why did you persist?

Well, I had that certain drive and conviction that nothing could be in my way. But I must say this: they were terrific teachers, very severe but very good, very good. They never liked what you did of course. And I once did a self portrait which was obviously done by myself. The professor came in and said: “Who did that awful self portrait?” (laughing)

Just by the way of finishing I would like to ask you: are you involved in activities as a social human being in the society you live in? In the news, the …what interests do you have that take you out of the studio?

Well, I go very much to museums.

But that’s almost too closely related to yourself.

Yes, it is. Well, I am member of the National Academy and the Audubon Society and this sort of thing. I think it’s all the same. It goes with the studio and with the work.

So you have never been thinking you could have been a musician instead of a painter?

No, I could never have been a musician.

Or anything else? An architect maybe?

I thought about that in the beginning. But I found out very, very quickly that painting is it. That is it.

And that is what you are going to end up with?

Exactly. Absolutely.

Thank you Eric Eisenburger!

Isenburger! (laughing)

Isenburger…

This interview was made on September 12th 1975 in the studio of Eric Isenburger in New York City.